American Psycho is More Than its Bad Reputation

How this controversial novel became a pop culture icon

I recently read American Psycho by Bret Easton Ellis for the first (and most likely last) time after having it in my possession for months. It’s not that it took me so long to get through it, but rather I was mentally preparing myself for the visceral journey. Why would you want to commit to such a thing if you knew that it would be so emotionally draining? I hear you ask. Well, even if you haven’t read it, or seen the movie, you’ve probably at least heard of it, right? That’s why I wanted to read it. I enjoy seeking out controversial art and finding meaning in what most people are afraid to confront, so I figured that I’d give it a shot. And boy, was I in for a wild ride.

One word comes to mind when I think of American Psycho: Excess. Everything from the lifestyle of protagonist Patrick Bateman, a 27-year-old sociopathic Wall Street accountant and recreational serial killer, to the prose itself is utterly exorbitant. He identifies everybody he encounters by naming their designer clothing and ruthlessly scrutinising their physique. Only the highest standards are acceptable for such a man, who frequently dines at prestigious new restaurants and takes copious drugs just to function. The ravenous sex and violence also goes into excruciating detail, written in the first person so that you, the reader, are privy to his sickening inner thoughts. Perhaps a better description for the novel would be experience.

It’s certainly not for the faint of heart. As a hardcore horror fan, I like to think that I’ve developed a tolerance for gore onscreen. But when it’s in writing, you’re left with your own imagination, which is often much worse. I mostly read at night, an hour or so before bed, so I wasn’t exactly lulled to sleep when reading this. In saying that, I certainly don’t regret reading it, which may seem counterintuitive for such a contentious creative work. This made me wonder why the book is so revered today, having sold over a million copies since it was first published in 1991 and later being adapted into a feature film in 2000. So, if it’s as bad as people say, how did this controversial novel become a modern classic?

What Does It All Mean?

As the title suggests, American Psycho is a satirical commentary on privileged white American males. Ellis implies, with devilish subtlety, that this stereotype is interchangeable among the elite by having characters constantly confuse each other for somebody else, which is where the black comedy comes in. Patrick Bateman is a despicable character. He is completely self-absorbed and materialistic, but also knowledgeable and witty, though Ellis ensures that we never truly resonate with him by making us feel complicit. Emotionally detached and increasingly apathetic, Bateman shamelessly carries out these heinous acts and indulges in debauchery with either great or zero pleasure.

American Psycho has become synonymous with toxic masculinity. It’s very misogynistic and explores the candid objectification of women, who are mostly referred to as “hardbodies.” As far as Bateman and his “yuppie” buddies are concerned, the only things that matter in life are getting richer, getting fucked up, and getting laid – in that order. Not only does Ellis write Bateman’s interactions with females from the perspective of the Male Gaze, he reduces them to mere playthings. I’ve read books with this tone before, such as Diary of an Oxygen Thief by Anonymous, but it’s dialled it up to eleven here.

It also has strong themes of obsession, vanity, and entitlement. Interestingly, it portrays the arrogant male characters as both proud of and deeply insecure about their self-image. Bateman has meticulous skincare and workout routines, gets regular manicures, and is frequently complimented on his fake tan. Bateman fears humiliation more than getting caught, casually killing people in the street and confessing his evil deeds mid-conversation without anybody noticing. This feminine side to the vulgar personalities exposes a shared vulnerability between predator and prey.

Bateman closely monitors The Zagat Survey, religiously watches The Patty Winters Show – a fictional daytime talk show covering outlandish topics – and idolises Donald Trump as a fellow racist and homophobe. This makes the novel relevant today, with Trump now in presidency for a second term in a bleak online society of herd mentality. It offers the reader a glimpse into a life of luxury and flaunted opulence while demonstrating how it erodes humanity. Perhaps the best example of this is Bateman periodically withdrawing cash from automated tellers just to feel it in his gazelleskin wallet. Ironically, he is disgusted by those of a lower status than he, just as the reader is by the character himself.

What’s So Good About It?

From a technical perspective, I love how Ellis italicises certain parts of words in dialogue to convey the tonal inflections of the characters. For example, a character might say that something is expensive. One chapter in which Bateman is experiencing a severe panic attack is almost a whole page written as a single sentence without indentations to create a sense of losing control. The novel in general is painfully descriptive and goes into great detail, especially when Bateman is having sex with two women at once then tortures them before finally killing them, which happens on multiple occasions. The sights, sounds, smells, and even tastes are disturbingly specific and really put the reader there with him.

There are also random chapters throughout where the author, as Bateman, waxes lyrical about particular musicians. He professes his admiration for Phil Collins, Whitney Houston, and Huey Lewis and the News, detailing the highs and lows of their careers and analysing their biggest hits. This is presumably to portray Bateman as a die-hard fanatic and obsessive consumer; somebody who is capable of appreciating great art, which may or may not be a subtextual reference to the author himself. In fact, the character is very much self-aware and doesn’t quite know what to make of it.

Here’s an excerpt in which Bateman accepts his true nature that possibly best summarises the concept of the novel:

There wasn’t a clear, identifiable emotion within me, except for greed and, possibly, total disgust. I had all the characteristics of a human being – flesh, blood, skin, hair – but my depersonalization was so intense, had gone so deep, that the normal ability to feel compassion had been eradicated, the victim of a slow, purposeful erasure.

Notice how he refers to himself as a victim. As the reader, you don’t want to resonate with Bateman’s perceptions of the world or laugh at his crass jokes, but Ellis’ effortless prose makes it so that you can’t help it. Before long, you find yourself eagerly turning the page to find out what happens next, then catch yourself and stop to have a good think about what you’re doing. I laughed out loud when reading a chapter in which Bateman is waving at a homeless person from the window of a taxi before suddenly giving them the finger, or holding money out to another then spending it on food and eating it in front of them. It entertains you then makes you feel bad for it, which is so sneaky that it’s genius.

Why is It So Contentious?

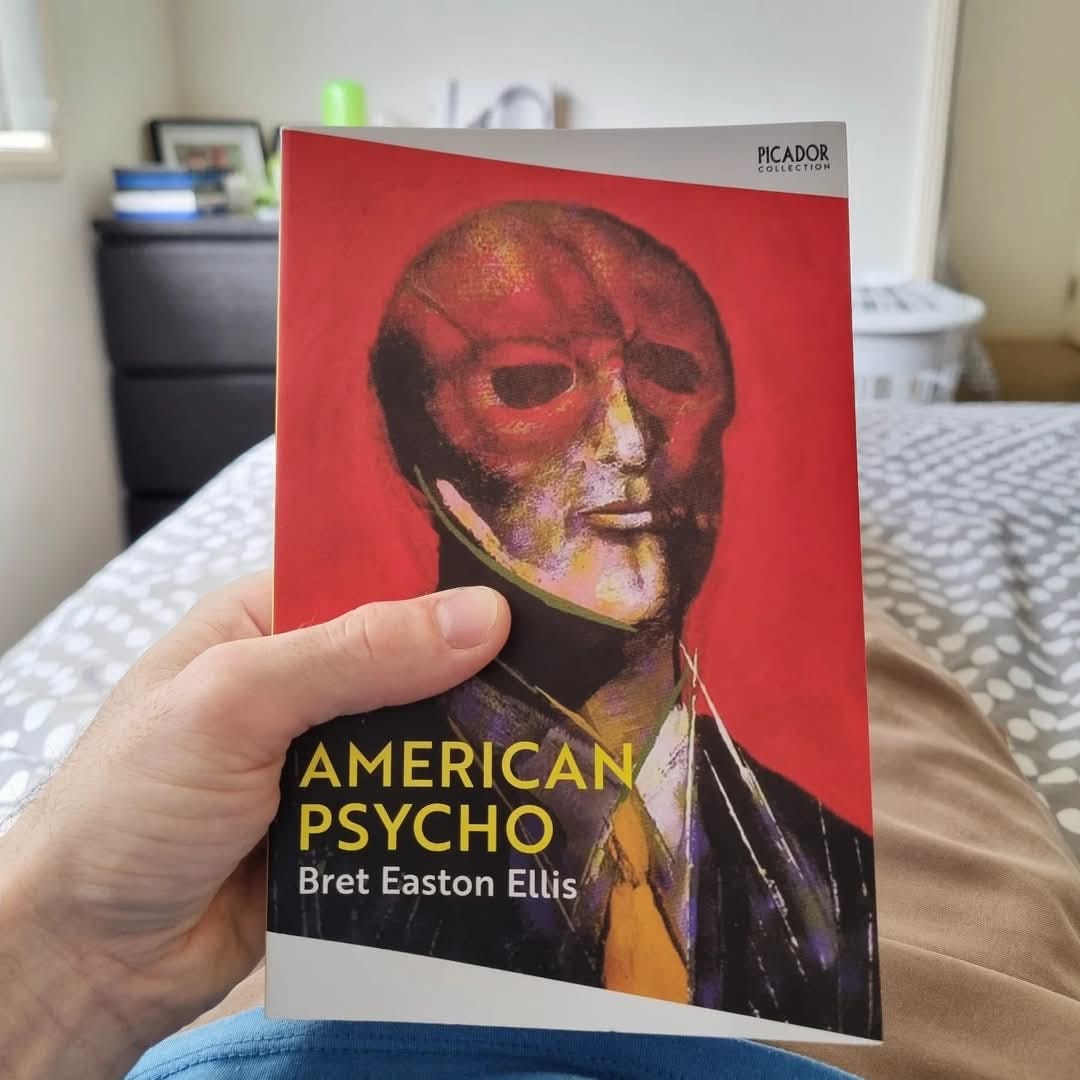

Of course, the reputation of American Psycho (unfortunately) precedes it, so now it’s difficult to separate the book from the author. So much so that it’s banned in Queensland, my home state of Australia – I bought my copy, shrink-wrapped, in New Zealand. But history has shown us that when a creative work sparks outrage and sets a new trend, it’s almost always necessary. Consider Brave New World by Aldous Huxley or Lolita by Vladimir Nabokov for example, both of which have also been banned in numerous countries and adapted for the screen. This satirisation of harsh truths is inevitable and censorship has evidently never worked. We don’t need to make Fahrenheit 451 a reality…again.

In the late 20th century, it was Bret Easton Ellis’ turn to take the fall. Having published the successful novels Less than Zero and The Rules of Attraction before American Psycho, he had already begun turning heads and raising eyebrows. While the values in his magnum opus may not be those of Ellis himself, there have been many people like Patrick Bateman before it and there will be many more as long as capitalism reigns. Art imitates life imitates art – and life isn’t always a pretty picture. Even the controversial The Anarchist Cookbook by William Powell is available to download for free online and you can buy Adolf Hitler’s autobiography Mein Kampf from most commercial bookstores. Which would you rather read?

It’s safe to say that American Psycho caused quite a stir in the press, but that was also kind of the point. We generally flinch when artists hold a mirror up to society and condemn them for it, yet this is the monster that we’ve (they’ve?) created. However, it’s easy for a creative work to be misconstrued when taken out of context.

Here’s what Ellis had to say about the novel in an interview with the Paris Review in 2012:

Months before the book was published, a few pages of the manuscript were leaked to the media, and these were the pages in which Patrick Bateman kills women, or fantasizes about killing women. The critics who read these pages naturally assumed they were representative of the whole book…

In fact, the outrage was so severe that Ellis began receiving death threats before it even hit shelves:

Some of these threats included drawings of my body, and people describing how they were going to torture me, and what they were going to do to my corpse… But when the book came out a few months later, the controversy stopped… People finally read the book, and they found out that it wasn’t four hundred pages of torture and mutilation and advocating the death of women. It’s just some boring novel.

Isn’t it funny how quick the public was to judge, threatening the author of a fiction novel with punishments similar to the crimes of its despicable protagonist? As Leo Tolstoy famously said: “A real work of art destroys – in the consciousness of the receiver – the separation between himself and the artist.”

I wasn’t expecting to enjoy American Psycho as much as I did, and I’m not quite sure how to feel about that. I think that my reaction was akin to driving past a car accident: You can’t help but look. It’s not perfect, or enlightening, and I probably wouldn’t recommend it to anybody, but its ingenuity is undeniable. Of course, I can understand why some people might be offended by it, especially feminists. Even so, the sharp wit and scrupulous storytelling is exceptional, so it’s not hard to see why it developed a cult following over time. I guess it goes to show that you shouldn’t judge a book by its cover – even when it’s wrapped in plastic and banned where you live – or by what other people say about it.

I found it masterful.