How to Write Like Stephen King

The master of horror shares his tips and tricks for writing good fiction and balancing work with life

It’s undeniable that Stephen King is one of the greatest storytellers of our time, as well as one of the most prolific, whether you’re a fan or not. As of writing this, he has published 65 novels, over 200 short stories (some under the pseudonym Richard Bachman) and five nonfiction books. His works have been adapted into more than a whopping 50 films and 20 TV shows. In just the past year alone, we’ve had The Monkey, The Life of Chuck, and The Long Walk, all adapted from short stories by King, with Edgar Wright’s take on The Running Man due next month. Considering that his debut novel Carrie was first published in 1974, the fact that it’s still being adapted for the screen today after two existing films says a lot.

Aside from being fond of titles beginning with “The,” the Maine man behind classics like ’Salem’s Lot and Christine also loves his community. King has gifted a generation of readers and writers with a seemingly endless source of inspiration and entertainment, but his most valuable contribution is his nonfiction book On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft, first published in 2000. Part autobiography, part how-to guide, it covers everything from King’s childhood and early career to the tools of the trade and that fateful accident in 1999 which nearly killed him. Perhaps the best feature is that it never feels like King is speaking with authority, even though he is one. It’s more like chatting with an old friend, which is what all good authors are.

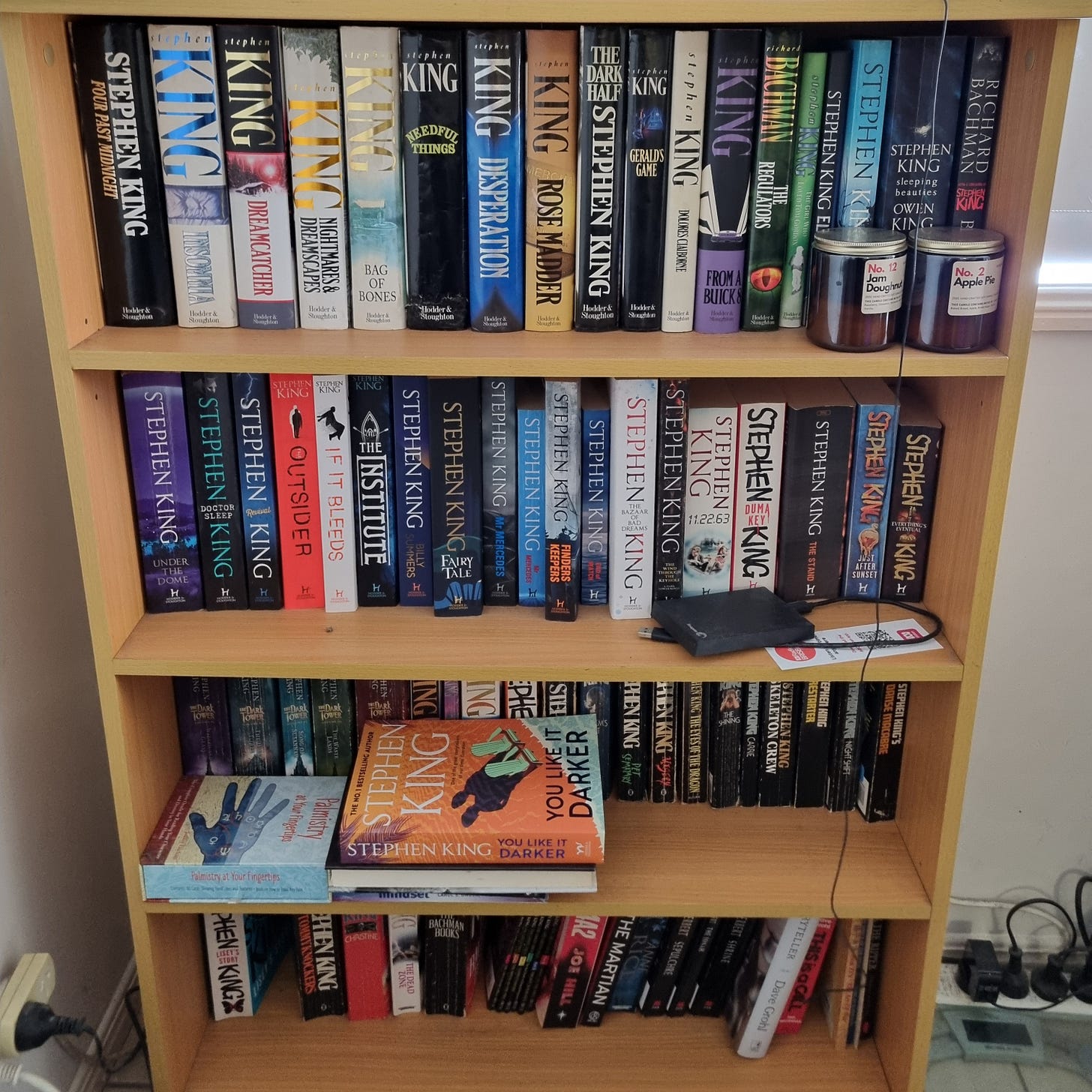

Before I get into what I learned from this book, I want to paint a picture of how my relationship with the master of horror began. I grew up in a household that admired his dark talent and my parents still have most of his books in a dedicated bookcase at home. Even though I’ve only read a handful of them (The Shining, Pet Sematary, Misery, and The Bachman Books), King has influenced my own taste and writing style as well. But first came the movies, which I understand the author had little do with in most cases – he famously disliked Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining (1980) and John Carpenter’s Christine (1983).

One of my favourite films as a child – it probably still is, to be honest – was Stand by Me (1986). In fact, it inspired me so much that I planned to run away with my best friends in the fourth grade for a weekend before we realised that it was ludicrous. We even had a list of supplies and everything. When I was a teenager, I saw epic dramas like The Shawshank Redemption (1994) and The Green Mile (1999) for the first time, but I always preferred the horrors. Pet Sematary (1989), It (1990) – Tim Curry is the best Pennywise and you can’t change my mind – and The Mist (2007) were some of the standouts.

As I got older and started to read more, I began to really appreciate the striking simplicity of King’s writing. He has some cool concepts, for sure. A killer car? Let’s go! A haunted hotel? Sign me up! A pyrokinetic primary-schooler? Hell yeah! It was like Goosebumps on steroids and even the cover art gave me chills. But his true ability is in creating good characters. I would always avoid dialogue in my own writing because it never felt natural on the page and all my characters sounded the same. When you read a King novel, you feel like you’ve known them all your life and you can hear the inflections in their phonetic phrasing.

If you’ve ever thought to yourself, I wish I could write like that, you’re in for a treat.

I read the twentieth anniversary edition of On Writing, which includes a new foreword titled On Joy, as well as contributions from his sons Joe Hill and Owen King, both of whom are also successful authors. In the opening passage, King – Stephen, that is – makes a point of saying that it was never about the money or the fame and he still loves what he does for a living. Even when he’s sick, hungover or recovering from a severe road accident, he writes. “The worst day I ever had was fucking great,” he says, and perhaps that’s the real key to his longevity in a creative career. If your work is play, you can do it forever.

In the second foreword (there are three all up), King also makes a point of saying that it’s a brief read because “the shorter the book, the less the bullshit.” I love his casual, no-nonsense approach and the constant references to other authors and books throughout. He even provides an extensive reading list at the end. It’s a fun breaking of the fourth wall, even though his personality usually comes through his characters, like when you hear your grandmother swear for the first time. But before he gets into the nitty-gritty of the craft, he ends the passage on his childhood and early career with some insightful advice:

“Put your desk in the corner, and every time you sit down there to write, remind yourself why it isn’t in the middle of the room. Life isn’t a support-system for art. It’s the other way around.”

So, here are what I believe to be the most valuable lessons in On Writing, based on what I underlined and highlighted along the way. (It seems fitting that there are 13, which is what you get when you add the numbers of the title 1408 – the reason why he called it that.)

Keep it simple

We’ve all read a verbose text in which the author waxes poetic for half the page in their finest assortment of adjectives and hyperbole – H.P. Lovecraft, I’m looking at you. King says that “one of the really bad things you can do to your writing is to dress up the vocabulary.” In other words, keep it simple. He goes on to say that the basic rule is to “use the first word that comes to your mind,” followed by some rather crude but amusing examples. If you just say what you want to say, how you would say it to somebody else in person, it will feel more natural to the reader and keep them in the world that you’ve created.

The shorter the better

This ties in with the previous tip and what King said about his own book (less bullshit). He shows that a sentence can contain as little as two words, a noun and a verb, and still be functionally correct. For example: “Rocks explode.” I love the punctuality of short sentences like this, especially when multiple are used in quick succession to build tension at a climactic moment in the story. This is also useful for dialogue, which he exemplifies by rephrasing “The meeting will be held at seven o’clock,” to “The meeting’s at seven.” Nobody actually talks like that unless they’re giving a formal presentation. Omit all unnecessary words.

Avoid adverbs as much as possible

King believes that excessive use of adverbs suggests that the writer is afraid they’re not expressing themselves clearly, and I think he’s right. He argues that, sure, they help to get the picture across as the writer perceives it in their mind’s eye, but is it necessary? Instead of forcing the reader to see exactly what you see, the context of the sentence when compared with the prose that comes before it should be enlightening enough to eliminate the need for describing how the action was performed. I sincerely hope that my strangely specific explanation makes complete sense. Got it?

“He said, she said”

A point that King stresses a lot is his (relatable) frustration with writers who feel the need to explore the murky depths of dialogue attribution. Instead of saying “‘Stop!’ Dylan cried,” “‘Wait,’ Stephen pleaded,” or “‘Why?’ the woman asked,” always, always, just use “said.” It sounds silly, but I really notice it now when I’m reading a book and the author explicitly tells me the way in which a character spoke. Similar to the last tip, he argues that if you’ve told your story well enough, the reader will know how it was said in the context of the situation. Have faith in their ability to discern between each tone and inflection.

Write it how it sounds

As I mentioned earlier, one of King’s greatest strengths is his characters and their dialogue. You can often picture a character by what they “sound” like. Write words phonetically so that the reader can hear them on the page. This is achieved with the use of contracted phrases like “dunno,” “gonna,” and, one of his personal favourites, “fuhgeddaboudit.” It’s also a great way to convey accents and impediments, such as substituting “there” with “thur.” King says that “language does not always have to wear a tie and lace-up shoes,” adding that it’s important to remember that “every character you create is partly you.”

Read and write a lot

If you want to be good at something, you’ve got to do it a lot – as simple as that. I’ve spoken before about balancing creative input with the output, if not more so, for new ideas to germinate. This is why musicians will often take time away from their work to replenish the well, so to speak. King argues that the only way to get better at writing is to write more, and the only way to develop your own style is to read as widely as possible. He says that we all inevitably adopt certain traits from our influences, but eventually we become an amalgamation of everything that we enjoy. At least one book a month should do it.

It’s a numbers game

The easiest way to improve your skills as a writer is not only to write often, but to have a consistent schedule. King famously dedicates four to six hours a day, every day, to his craft – even on birthdays and Christmases. He also understands that this isn’t always achievable for those who don’t write for a living, so he suggests putting a thousand words on the page each session if you can. My good friend Kody Roby, with whom I hosted a Q&A in August, took a similar approach to writing his debut novel Dead Man’s Detail. King goes on to say that the first draft of a book, even a long one, should take no more than three months.

Write in a room with a door

This one might seem a little obvious, but there’s actually a very good reason for it. King says that your humble writing room only really needs one thing: a door which you are willing to shut. You see, when the door is closed, you are free to write whatever you want without distraction or judgement. It’s much easier to meet your goal for the session if you have locked the rest of the world out. This may seem unhealthy (and potentially disastrous for your relationships), but it’s necessary for artists to work in solitude, at least occasionally. Only once the first draft is complete should you write with the door open.

Write what you want to know

We’ve all heard that limiting write-what-you-know directive countless times before. But if this were true, how do we have so much great fiction about monsters and magic? Michael Crichton, one of my favourite authors, did extensive research for his novels because he wanted them to be realistic. King says that most of his ideas have begun with asking what if… Come up with a scenario that would make for an interesting story, then draw from your personal experience and expertise to make it believable enough for the reader. In other words, write what you want to know. Or, better yet, recontextualise what you know.

Don’t do it for the plot

In theatre, there’s an old rule that states when a gun is introduced in the first act, it must be fired in the third. The same goes for fiction writing. King argues that a story consists of three things: narration (action), description (sensory details), and dialogue (characters). There is no place for plot in a good story because it should resemble the spontaneity of real life. Things should inevitably go wrong for your characters, just as it would for you or anybody else in their situation. Obnoxious plot devices that get shoehorned in for the sake of convenience are examples of lazy writing, and attentive readers will smell them from a mile away.

Show, don’t tell

As with avoiding adverbs and writing how it sounds, King stresses that you should “never tell us a thing if you can show us.” Give enough of a description for the reader to get an idea of what’s going on and how the characters are reacting, but don’t list it like an instruction manual. He also strongly advises against using vague clichés, such as “he ran like a madman,” or “she was hot as a summer day.” Only describe the things which are relevant to the story, not every minor detail. This goes for a character’s history, too. As King says, “we all have one and most of it isn’t very interesting.”

Symbolism and theme come naturally

King notes that symbolism emerges from the key points of a story and often only becomes apparent upon reading the first draft. Once you’ve identified any underlying patterns, you can bring them to the forefront in the second. He says that every good book is about something, and it’s your job to decide what that is as you go. It wasn’t until he revised Misery that King realised Annie Wilkes was a personification of his drug and alcohol addiction. He also says that he doesn’t know how a story will end until he writes it, which he assures us is half the fun. However, this may explain his notoriously bad ones – The Shining, for example.

When in doubt, cut it out

This is good advice in any creative medium, but especially useful for writing. Edits and revisions are a crucial part of the process, yet can also be the hardest. King says that the first draft should be written with no help or interference from anybody else (door shut), then shared with a very select few before beginning the second (door open). He also suggests waiting six weeks before revisiting the work to ensure that you return to it with a fresh perspective. The formula that he uses, which was apparently given to him by an editor when he was just starting out, is this: second draft = first draft – 10%.

You can tell from the way Stephen King talks about fellow writers, his family and his fans that he has unwavering faith in those who decide to pursue a career in the arts, especially those who support his own. It’s not an easy path; one of the hardest, in fact. But it’s also one of the truest and most fulfilling. My favourite quote from the book is on the second last page (before the updated epilogues):

“Writing isn’t about making money, getting famous, getting dates, getting laid, or making friends. In the end, it’s about enriching the lives of those who will read your work, and enriching your own life, as well.”

This is one of his best endings to a book, in my opinion. But what would I know? I’m just a blogger.

Stories that Stand the Test of Time

I recently read The Invisible Man by H.G. Wells, first published in 1897, and rewatched the classic 1933 film by the legendary James Whale to see how it translated to the screen. The original adaptation features some of my favourite practical effects, despite being over 90 years old, and

What I’ve Watched This Week

I’m back in Brisbane now from a week with family in Gippsland – it was literally double the temperature of where I came from when I landed – and I’m already missing that clean country air. We hiked through mountain ash forests, across old trestle bridges and to serene waterfalls. I watched a dozen wild king parrots feed in the birdhouse as the sun came …