The Life Cycles of Dead Formats

Why I don’t think CDs will make a comeback in the not-so-distant future

Let me open with the disclaimer that, as a 90s kid, I came into the world blessed with the abundance and accessibility of music on compact disc. I can also remember using floppy disks and VHS tapes in my childhood, both of which have since become relics of the near past, so I’m not completely unqualified to discuss “dead formats,” if it needs to be said. In any case, this piece will only explore the last 30 years of physical music from my own point of view as both a consumer and a retailer.

While Gen Z has only caught the tail end of the physical media evolution, I haven’t met too many people younger than me who even own any CDs or DVDs, let alone consider themselves avid collectors. An exception can be made for young Taylor Swift and Billie Eilish fans, who constantly clean out the vinyl section at my work. Now that music and film has essentially gone digital, with much made specifically for streaming, it got me thinking about the cyclical trends of media consumption and whether certain formats will, or should, stay dead.

After going on a road trip with my mum to New South Wales in 2006, I asked her to make me a mix CD of Def Leppard’s greatest hits – the first of a single artist. I remember sitting in the backseat as a kid playing burned copies of Linkin Park’s Hybrid Theory and Matchbox Twenty’s Mad Season – seriously, how good was the year 2000?! – on Mum’s Walkman. We made them seasonal, like our own So Fresh series, and giving people mix CDs would become my love language. Sharing the link to a Spotify playlist with somebody just isn’t the same.

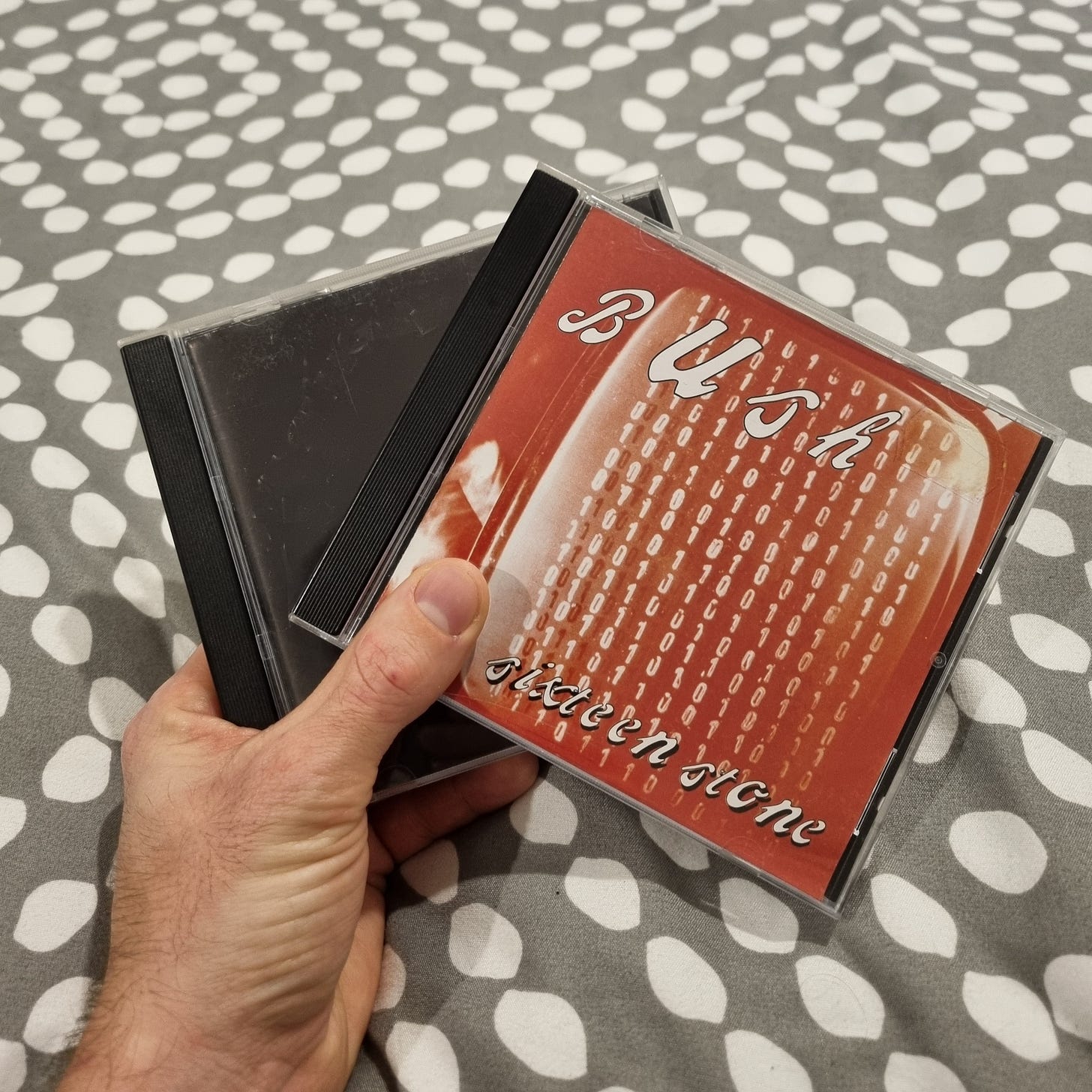

The first CDs I ever bought were Bush’s Sixteen Stone and Metallica’s Black Album. I eventually graduated to my very own MP3 player, which Mum loaded with everything from Motley Crue and U2 to Nirvana and blink-182. Meanwhile, ABC’s Rage on Saturday mornings introduced me to bands like Good Charlotte and Evanescence before I discovered Eminem and Jay-Z. Like most Millennials, video games like Tony Hawk’s Underground and Need for Speed: Most Wanted also informed my taste with the latest pop punk and hip hop.

Flash forward a couple decades and we’re in the midst of a vinyl revival, while CDs are reduced from prided jewel cases and digipaks to flimsy cardboard sleeves – or coasters, as I like to call them – for double the price. Even cassettes, which were most popular between the mid-80s and early 90s, have made a comeback in recent years despite compatible boomboxes being well out of fashion by now.

I think part of the reason that vinyl is once again so popular, at least amongst the hipsters (including me), is due to the many different forms it can take. There are colour variants, from smokes and splatters to transparent and glow-in-the-dark. There are hand-numbered, limited edition represses with alternative artwork. Hell, there are even records filled with anything from rose petals and bullet casings to glitter goo and human urine. Brisbane’s The Dream Division has given many local heavy bands the vinyl treatment.

What makes vinyl and cassette so appealing in the modern era is that they require a certain amount of effort to play. In an age of passive consumerism and instant gratification, these archaic methods allow you to actively engage with the music and listen with intention. You have to place the record on the turntable, set the speed and drop the needle, then flip it over halfway through instead of simply tapping a button on a screen. Not to mention the debate of quality, as few streaming services offer lossless audio and MP3 players store compressed files by nature.

In an insufferably snobbish kind of way, the friction makes the reward more satisfying. Moreover, vinyl is a collector’s item rather than just a medium for playing the album. You can even frame the cover and put it on a wall as the piece of art that it is. If you’ve ever left a record in a hot car, you’ll know that it’s possibly the only way to waste your money on music, unless you bought tickets to a Guns N’ Roses show back in the day. While cassettes, like CDs, are small, portable and encased in plastic, the tape is also susceptible to heat and easily damaged.

This is why I think that CDs will remain obsolete when they eventually cease to be manufactured. While CDs are compact – it’s in the name, after all – they’re easily played, skipped and replayed, which means that there’s no real experience in their physical use. Sure, they get scratched and warped, but at least writing on them doesn’t render them useless, so they’re somewhat robust in comparison to wax and tape. I usually wouldn’t say this, but the fragility of a material existence fundamentally increases its value in this case.

The only remaining value will be in the little booklets of lyrics and liner notes, but now they generally contain nothing more than production credits. Don’t get me wrong, this was very useful to me growing up as an aspiring rapper. I would learn the real names of my influences and find out who made their beats so that I could hit them up myself, some of whom went on to produce my own stuff. But unless you want to know where the tracks were recorded, or how many ways the streaming royalties will be split, they don’t offer much these days.

Another thing worth noting is how short albums have become due to the decline in physical media. When streaming was getting popular, I used to imagine that albums would have an unlimited number of songs without the limitations of wax, tape or plastic. Instead, artists and labels, especially independent musicians, gravitate towards EPs and singles for affordability and prolificity. There are some exceptions, such as Halsey’s 2024 album The Great Impersonator, which consists of a whopping 19 tracks, including a six-minute opener, but this is a rarity.

Perhaps the waning attention span of the average listener is to blame. Most contemporary songs are around three minutes long, with some radio hits, like Amy Shark’s 2023 single “Can I Shower at Yours?”, clocking in at less than two. Gone are the days of guitar solos and extended intros in commercial music. You can’t even resurrect the hidden track unless you bury it in the closer beyond minutes of silence like it’s soured soil, which will most likely be skipped anyway.

For example, Metallica’s 1986 album Master of Puppets has a runtime of 54 minutes and 52 seconds over just eight tracks, whereas Bring Me the Horizon’s 2024 album Post Human: NeX GEn is about the same duration with twice as many tracks. (I understand that these two bands are vastly different, with albums released nearly four decades apart, but they can both at least be considered commercially viable “metal” for argument’s sake.)

The streaming model is all about finding singles for playlist curation rather than “enduring” whole albums. Just look at the dismal number of plays as you go down the tracklisting of an album on Spotify. For indie artists, it’s more lucrative to release songs individually then promote and tour them consistently than it is to have a traditional album cycle these days. But as any musician will know: if you’re in it for the money, you’re in the wrong industry. Besides, they can always have a physical release at a later date for the die-hard fans.

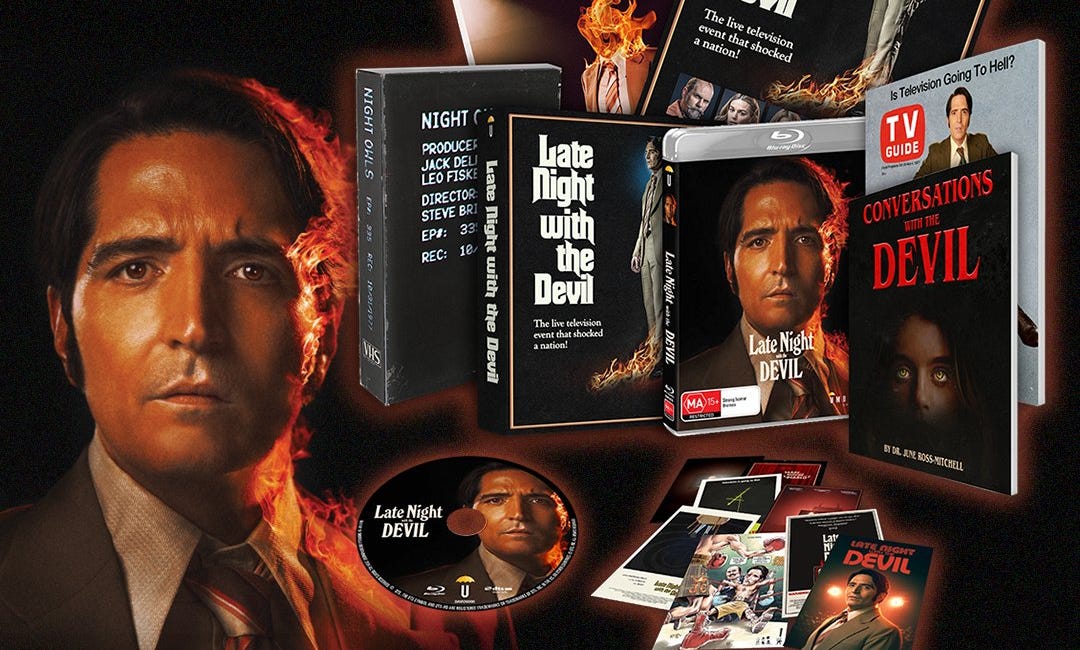

Nowadays, most of my money is spent on movies and books, the latter of which is usually pre-owned. I can stream pretty much all of my music, even if I have to play it via YouTube, but I can’t find every film online. Thankfully, distributors like Umbrella and Criterion have incredible releases and are dedicated to restoring aged classics. Even movies have evolved from videos to DVDs to Blurays to 4K discs. I support my favourite artists by attending their live shows and buying merch instead, which pays them more than streams anyway.

As I’ve said before, I decided to stop buying CDs this year when I moved house for the fourth time in five years and realised how cumbersome they had become. Maybe this reluctance was due to a sunk-cost fallacy, but I’ve been justifying my purchases lately by only buying something if I’m likely to use it in the next month. I halved my collection and either gave them to friends or donated them to op shops. Now, I only pick up the odd vinyl here and there, especially on Record Store Day, but I still don’t even have a turntable.

As somebody who can’t stand clutter and who also just bought a new pair of wireless headphones, I should probably stop resisting the change. Digital media obviously has its benefits, from accessibility and affordability to variety and, at times, quality. Although even these alluring features can depend on your internet connection and an unreliable streamer. Perhaps it’s the warm feeling of nostalgia, or the powerful sensation of ownership that comes with holding my favourite art and displaying it on a shelf, but I can’t let them go just yet.

So, when CDs are to my grandkids what vinyl is to me, they just might stay dead.

Do I Make Art for Me or You?

J.D. Salinger, author of The Catcher in the Rye, which I recently read for the first time and loved, once said “an artist’s only concern is to shoot for some kind of perfection, and on his own terms, not anyone else’s.”

Why Physical Media is Better than Streaming

It’s undeniable that niche physical media sales have seen an upward (albeit slight) trend in recent years. Thanks in part to both the hipster counterculture and Taylor Swift, people are actually going out and buying discs and vinyl records again. In the digital age, it’s easy to be swept up in the riptide of online streaming services, not to mention the…