Welcome to your Sunday Fluff at The Drip Tray: a weekly treat of fun and fandom to indulge your sweet tooth, like an artsy latte.

The first movie that I ever saw at a cinema was Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets (2002), a 161-minute fantasy adventure with a giant basilisk that scared the crap out of five-year-old me. The last movie that I saw at a cinema was a retro screening of the sci-fi action classic Aliens (1986) – the Director’s Cut, no less – with some friends last weekend.

When I was a teenager, we would get dropped off by our parents and run amok at the arcade before catching the latest horror, action or comedy film. We would take our seats, usually in the middle of the back row, and dig into a bucket of popcorn with our eyes glued to the big screen for a couple hours. Now, we drive ourselves and sip coffee instead.

So, with the decline of physical media sales and the rise of video on demand, what makes going to a cinema worth it when you can just watch it at home?

First of all, it’s an experience. The big projector screen, the booming surround sound, the comfy recliner seats – this is how movies are made to be enjoyed. Not played absently in the background while you fuss about in the kitchen or squinted at on your mobile phone during your commute to and from work. There’s something about sitting quietly with strangers in the dark and immersing yourselves in a story together that just feels so transient and gratifying.

It’s the jumps, the laughs, the screams, the tears, the goosebumps. All the visceral reactions from the audience bouncing off each other in a confined space. You become fully aware that you are one of many who are feeling this way and will, in some cases, leave the room changed. I remember seeing Avatar (2009) in 3D and thinking that I was part of something special, then later recognising Get Out (2017) as a significant moment in 21st century horror.

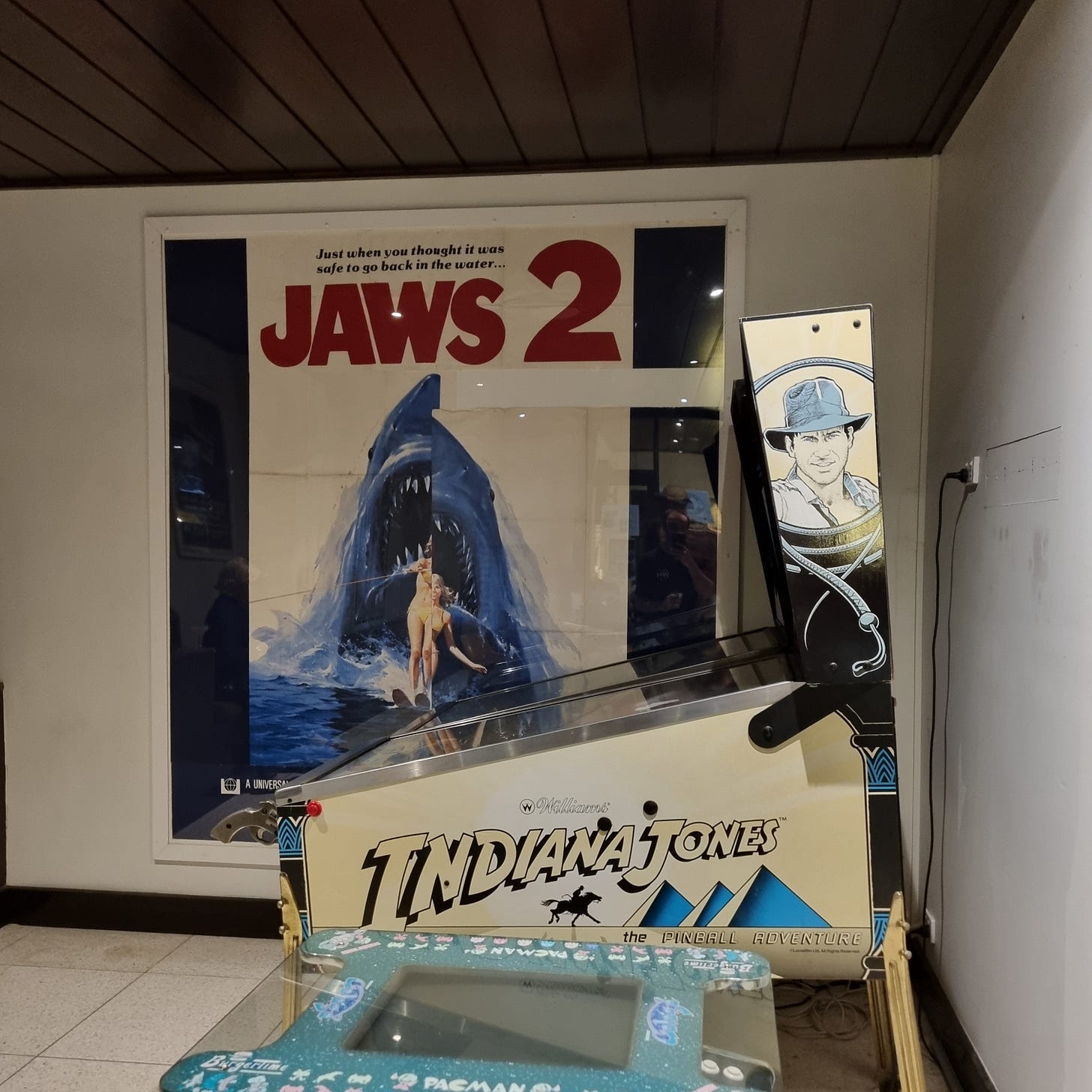

I live an hour north of Brisbane and willingly drive the distance to an indie theatre there every fortnight or so for experiences like these. Five Star Cinema at New Farm is an old building with traditional lighting and flooring. They even have chalk art on blackboard frames out the front! As you enter the lobby, stairs lead to a bar area adorned with old movie posters, classic pinball machines and beach chairs for some reason.

You collect your ticket and find the cinema, distinguished by colour rather than number, which all have open seating with soft leather chairs. Five Star regularly host advanced and retro screenings, filmmaker Q&As and even tours of the projection booth. You can get cheap tickets by becoming a member and all the patrons are fellow cinephiles. Oh, and there’s a 24/7 coffee shop with an alternative aesthetic called Death Before Decaf across the road.

Secondly, leaving the house to go see a movie is more intentional and therefore more valuable. When you’re sitting in a dark room with other people watching a film that you paid for, you can enjoy it uninterrupted and without the distraction of your nagging phone or children. It’s a great way to disconnect from the world and dive into another one, although I’m still mindful of how much screen time that I allow myself in a day.

On that note, everybody’s there for the same reason. I remember the strangely comforting transition from high school to uni because we all wanted to be there. Well, this is the same logic. There’s nothing worse than chewing up an emotive or tense scene at home when somebody enters the room and cracks up laughing or belches loudly and asks what you’re watching. At least at the cinema, the audience is respectful for the most part.

Another really cool benefit of going to the movies is that you get to see a fresh feature before it hits the streamers. Some people prefer not to spend their money on a gamble and just wait until it lands on Netflix or Stan, but that’s part of the fun! Take a risk and see it in the best possible environment – big screen, surround sound, comfy seats – for a first experience. If you don’t know what it’s about or who’s in it, that’s what trailers are for.

This is also a great way to support independent filmmakers and contribute to a film’s success. The opening weekend determines the length of its theatrical run, so by waiting until it reaches VOD or gets a physical release, you’re doing it a disservice. It’s like when an artist plays a show in your hometown and you miss it then regret not going, except that films don’t usually come around again. Besides, even if it’s terrible, at least you will have tried something new!

Lastly, do it for the culture. Here in Australia, you can go to your local Event or Hoyts and catch the latest blockbusters, or find a more bespoke Palace or Dendy to see what might have gone under your radar. Every cinema visit helps to keep the industry alive and is an opportunity to relish this beloved connection to the past. It’s something that my parents and grandparents did growing up, and hopefully a tradition that I’ll pass down myself someday.

Of course, streaming obviously has its benefits. It’s convenient, it’s cheaper, you get more targeted ads, you can get subtitles if you’re not paying attention and watch on an OLED if you have one. You can’t always get to a cinema when a film that you want to see is showing anyway. But you’ve also got to contend with limited availability, content that can be pulled at any time, buffering, dynamic audio and, unless you have a decent media room, a confined space to enjoy it in.

I know which I’d prefer – and, thankfully, I’m not the only one. Here’s what my good friend and fellow cinephile Pace Proctor of Not Another Film Blog has to say about the cinema experience:

I’ve always loved film. Whether it was family movie nights after trips to Blockbuster, wearing out my Spider-Man (2002) VHS by rewinding fight scenes with my cousins, or nervous first dates at the cinema, movies have been a wellspring of communal experiences that have shaped my life.

The post-movie debrief from the lobby to the car ride home, the quiet moments of awe and anticipation, and the collective laughter, sadness, or even trauma enabled by film have made me a believer in the elusive concept of movie magic.

I say all this to establish three things. First, I love devouring films in any form—whether on the big screen, a late-night TV broadcast, or a long-haul plane ride. Second, I don’t hate streaming or watching at home. But lastly, and most importantly, how we engage with film—its distribution, its interaction, and the way it’s experienced—matters. It shapes its value as an artform, our connection to it and, ultimately, its place in our lives.

My fear isn’t just that fewer people will go to the movies; it’s that fewer movies will be made for the movies. If we stop watching films in cinemas, studios will stop making films worthy of cinemas.

Without cinemas, we won’t make movies that demand the big screen. The old Hollywood studio system was built to manufacture films at record speed, yet it still delivered spectacle and quality. We’re still quoting those movies today, for crying out loud. Yet, for all the innovation, we’re still making slop. Here’s looking at you, Netflix.

We let the genie out of the bottle and wished for everything at our fingertips. The monkey’s paw curled, and the movie magic disappeared. Decision fatigue and the second-screen economy set in so subtly that it was hard to even notice.

The modern commodification of film for streaming services has plunged us into a dark age, with no enlightenment period in sight. Watching a movie alone on your laptop is like riding a rollercoaster by yourself—it might still be fun, but the collective thrill is missing.

The cinema is our modern-day campfire, where we gather to hear and see stories told on a grand scale. It’s where crowd-pleasers fund the niche and arthouse films, ensuring a diverse cinematic landscape. Streaming, by contrast, has devalued film in a way we’ve never seen before.

For the first time, movies are being consumed not as an experience but as disposable content—background noise to be half-watched while scrolling your phone. Sitting on someone’s couch watching it on a flatscreen wouldn’t have given me the religious, spiritual, awe-inducing effect of seeing a story projected onto a massive screen in a darkened room.

There’s a reason churches are built the way they are—vast, immersive spaces designed to make you feel small in the presence of something greater than yourself. The cinema operates on the same principle.

So yeah, I’ll defend $17 popcorn and sticky floors, because when we buy a ticket, we’re not just paying to watch a film—we’re placing a bet, making an investment. And in doing so, we demand something in return. That’s the difference. When a movie is bad, we feel it in our wallets, and that sting matters. It’s what makes us voice our opinions, what should push studios to do better, and what ultimately shapes the future of film.

The Greatest Aussie Movie Villains

Welcome to your Sunday Fluff at The Drip Tray: a weekly treat of fun and fandom to indulge your sweet tooth, like an artsy latte.

Nostalgia Has Hollywood in Retrograde

Welcome to your Sunday Fluff at The Drip Tray: a weekly treat of fun and fandom to indulge your sweet tooth, like an artsy latte.

I definitely need to get to the cinema more often! Thanks for the reminder.